“I want my daughters to be beautiful, accomplished, and good; to be admired, loved, and respected; to have a happy youth, to be well and wisely married, and to lead useful, pleasant lives, with as little care and sorrow as God sees fit to send….”

– Marmee in Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women (Chapter 9)

I am sure any boy who grew up reading books, and had sisters, occasionally borrowed one of his sister’s “girl’s books” to see what they were about, whether he would admit it or not. This was how I read the Little House books of Laura Ingalls Wilder. This week I decided to take a look at a “girl’s book” I had never gotten to, Little Women. To a boy the title of the book alone would probably be enough to put him off; but as a traditionalist American I thought it would be worth seeing what the book had to say about the American Woman.

Until a few decades ago, Americans lived and expressed themselves within a white and culturally Christian society with clearly defined gender roles. Now that immigration, multiculturalism, and feminism have destroyed this norm, it can be hard to imagine what life was like under it. Many younger people, I am sure, are convinced that America was a backwards and bigoted society. Older people, too, have mainly accepted the “progress” we have made since their youth (if not, they have at least decided not to say anything). Yet sometimes, when we encounter our past in history, film, or literature, a strange feeling nags at our hearts and tells us that it is not so.

I believe that though this feeling lies hidden in our society, unformed and inarticulate, it is real and part of all of us, even those too young to have direct memories of the traditional America. I have sensed it in my mother, who has spoken nostalgically of playing in her wooded neighborhood with other children, free of adult supervision but secure in the nearby presence of mothers and a community one knew well. I saw it in the response of an older woman to a musical about the life of the Andrews Sisters. Nothing explicit, just words like “They don’t make music like that anymore.” But the real meaning went so much farther. They don’t make society like that anymore. They don’t make women like that anymore. That’s why they don’t make songs like that anymore.

Of course, I don’t mean literally that today’s women are of lower quality than our grandmothers and great-grandmothers! But girlhood, womanhood, and femininity lack a cultural expression today, outside of rare occasions like weddings. In education and culture of the present day, the ideals held up for women are the same as those traditionally applied to men: leadership, independence, assertiveness, adventurousness, athleticism. And we have lost utterly a picture of an ideal woman – an image of feminine beauty, modesty, taste and sensitivity, nurturing care, and other qualities that could be expressed through language, dress, and behavior and embodied in the culture.

The same can be said, of course, about men and the masculine virtues. However, while it is not so hard to imagine making changes in our society along traditionalist lines to improve the quality of our men, it is more difficult to envision the form in which feminine virtues might be restored. Few women would want to return to the cumbersome outfits of the past or be limited to the roles played by women in 19th century farming families or 1950s nuclear families. For this reason, my view of women’s role in a revived traditionalist society is minimalist and fair. Namely, that a woman’s life course should involve a traditional, lifetime marriage and children. (This notion is by its nature reciprocal, since it would have to apply equally to men.) I believe that to implement this in practical terms would mean the restoration of certain gender differences and inequalities. I do not believe it would lead to the loss of most of the career opportunities that exist for women today, although we might well return to male (and female) dominance of certain professions and leadership roles.

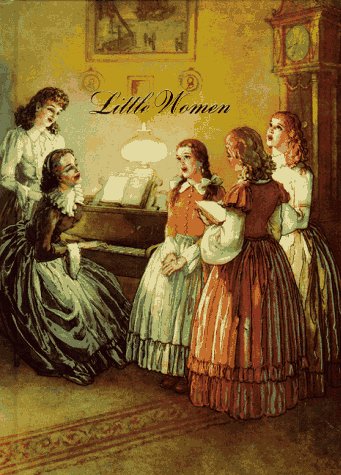

While it is impossible to go back to the past, the art and literature of the past can help us to understand what is possible. Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women (1868) portrays a group of sisters representing idealized types of girl, each with her own type of beauty and particular virtue, and also with her particular weakness which she battles throughout her life. Thus Meg is nurturing and beautiful but vain; Jo enterprising and creative but quick to anger; Beth musical and self-sacrificing but shy; and Amy sweet and artistic but spoiled. The book is composed of various episodes, each of which typically involves one of the girls learning a life-lesson on the need to control one’s temper, avoid envy and pride, work hard, be charitable, and so forth. (Little Women actually uses Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress as a reference for the girls’ journey through life.) Alcott herself was a kind of feminist and “literary spinster” who identified with the “tomboy” character Jo and expressed dissatisfaction with churning out “moral pap” for girls. Despite this, the book conjures up a sweet and beautiful world, where expectations for future lives as wives and mothers give a meaning, shape, and kind of sacred quality to the girls’ work, play, and education.

A critic could, of course, call the book false, a romantic fantasy. Even if this is so, the type of fantasy a society creates says something real about its soul. And in Little Women one sees a deep love between sisters and between mother and daughters that is utterly free of feminist distortion and resentment towards males. So, too, it was innovative as an early form of the American “domestic novel.” In the words of Madeline Stern:

Little Women is great because it is a book on the American home, and hence universal in its appeal. As long as human beings delight in “the blessings that alone can make life happy,” as long as they believe, with Jo March, that “families are the most beautiful things in all the world,” the book will be treasured. (1)

The values held by the March family amount to a uniquely American conglomeration of stern Calvinism and English bourgeois values: a strong work ethic and a dislike of the pursuit of money, ostentation, and habits like drinking and gambling; but a very worldly enjoyment of art, music, games, nature, and conversation. Here we find the moral values at the core of America’s greatness, but also the seeds of America’s future sacrifice of everything it has and is to non-Western “humanity.” When the March girls sacrifice their Christmas breakfast to a poor German woman with six children, we see the native American sense of charity in all its sweetness, but we may also note how easily such an impulse could morph into suicidal liberalism.

Most delightful in reading this book is to experience the drama of life, love, and family as it plays out in a world lacking the distortion of multiculturalism. The girls can be themselves and can sort out their friends and suitors on their own merits; there is no discussion of the need for “tolerance” or “diversity,” themes which doubtless would feature prominently in any novel written for the same age group today. The same could be said of most pre-1960s art and literature of the West. There are no racial tensions whatsoever in the book because there are no racial minorities present in the society of the Marches – even though they are the sort of family that would probably invite a poor “colored” man to dinner; even though the father is away from home serving as a chaplain in the Civil War! And though modern critics would attack the book for “suppressing” the black, American Indian, homosexual, and other “marginal” viewpoints, the truth is that the March girls are just being themselves. They live their own lives in their own society, and it is because their society is relatively homogeneous that they are able to live with a sense of higher meaning, struggling to do good and develop as women, within the common understandings of that society. Such, at least, is the thought that strikes me in reading Little Women, a story set in a world that is so far away from and yet so close to our own.

Notes

(1) Madeline B. Stern, “Louisa May Alcott: An Appraisal,” The New England Quarterly, Vol. 22, No. 4 (Dec., 1949), p. 476.

Stephen,

A lovely piece about a work of literature I enjoyed very much when I was young.

I’d like to refer to it over at Kinism.net, if that’s all right with you…

God bless,

Laurel

Laurel, thank you! Yes, please feel free to refer to it at Kinism!

I am interested in what the ladies have to say about this subject…!

By the way, if you have other favorite American female writers/figures you think the Heritage American should cover, let me know. The women remembered today (including Alcott) are remembered mostly for their “liberal” tendencies….

Very nice piece.

I read Little Women long ago as a child. Back then every girl read it, and I suspect it’s still a fairly popular work among girls, especially because it can be seen as some kind of proto-feminist work. At least it isn’t seen as anti-feminist as many older works are.

One thing I’ve noticed in recent years: when I talk to other women about Little Women, they always, always say they were ”just like Jo” when they were girls, or at least that they ”identified with Jo.” I suppose Jo is seen as the budding feminist in the book.

I agree that the ‘new America’ which is in opposition to the old America of Alcott’s day has pretty much burned its bridges to the older standards of feminine virtue, and it would be a real challenge to try to reinstate those old ideals, much more of a challenge than reviving the old male virtues, as you say. But I think perhaps any kind of renaissance would have to begin with men reclaiming their rightful role and then we might work from there.

As far as American female writers of the ‘old America’, at least those of my childhood, I remember reading avidly the books of Maud Hart Lovelace. She was later than Alcott, being an early 20th century writer. Her books were about girls in small-town Minnesota. I can’t say whether she was a literary great, but her books were popular and I loved them. I expect they were part of the childhood of many little girls up to the 1950s and 60s, but I think her books are out of print now.

What about Margaret Mitchell? Unlike many women I do not adore ‘Gone With the Wind’ but many women seem to.

-VA

VA, thank you. I thought the subject would interest you!

Your comment about women saying they were “like Jo” is funny because when I mentioned Little Women to my wife, who has not read it, her main impression came from a woman friend who also identified with the Jo character. I guess that has become a “meme”….

Of course, it could also simply be that Jo, as Alcott’s alter-ego, is the most “real” character. And it may be hard for a girl today to relate to any of the others. “Oh, I was just like Beth…”

Re: recovering the virtues: so, men need to take charge here, huh? :-)

Maud Hart Lovelace…I see she wrote historical novels too. I’ll take a look. Thanks for the suggestion. And yes, the Heritage American should tackle Gone With The Wind sometime….

“Little Women” didn’t depict “traditional” womanhood at all. The March family was atypical for their time. The mother and some of the daughters worked outside the home (which was unusual even during a time of war), the family favored education for girls, the parents didn’t believe in corporal punishment (even removing Amy from school because of it), favored equality of the sexes, and encouraged women to pursue careers (also unusual for the time).

The Alcotts themselves were anything but traditional! They belonged to a radical religious sect and Alcott herself spent most of her life working for women’s suffrage.

HHinson,

I am not arguing that Little Women is a “conservative” book; it was certainly liberal for its time, and the Alcotts and the New England intellectuals were liberal and even radical. Any scholarly article about Little Women written today will emphasize that and Alcott’s own feminist tendencies. What I am trying to show is that the ethos of the book remains that of a white, Christian society centered on marriage and holding clearly-defined gender roles or at least, as I call them, gender-specific “virtues.” Alcott herself may have felt forced to alter what she really wanted to write to meet the standards of her society, but that does not change the nature and value of the resulting work. In our advanced liberal society, even Little Women appears conservative!

Also, (though I’m not sure whether you’re disputing this) what I am calling “traditionalism” refers to a set of social values which recognize categories of existence that transcend the individual, e.g. gender, age, race, nationality. It does not mean the rejection of individual choice and equality under the law, and does not inherently preclude things like women’s education and women working outside the home. Like some other conservative thinkers, I view this sort of expansion of choice for women as something made possible by things like the civil order and the economic prosperity of a modern society, and not necessarily as the achievements of modern liberalism and feminism.

I am not very surprised, ____ , but the audacity and disrespect of the “adapation” you describe is beyond what one could imagine. Thanks for the tip.